The first digital pianos retained some of the other capabilities of their parent instruments by including a few preset voices besides that of the acoustic piano. It wasn’t long before subsequent models appeared with expanded voice capabilities, reverberation effects, background accompaniments, the ability to connect to other digital instruments and computers, and much more. In this article we’ll look at each of these categories of “extras,” what they do, and how they might enhance your musical experience.

Instrumental Voices

The designers of the first digital pianos correctly assumed that someone who needed the sound of an acoustic piano would probably benefit from a handful of related voices, such as the harpsichord, an organ sound or two, the very different but highly useful sounds of such electric pianos as the Fender Rhodes, and so on. To this day, even the most basic digital pianos feature voice lists very similar to those of the original models. What’s changed over the years is the quality or authenticity of those voices, and the cost of producing them.

So far, in Part 1 of this article, I have discussed only samples of acoustic pianos. For most models of digital piano, the same sampling technology is used to reproduce the sound of other acoustic instruments. Typically, an expanded selection of high-quality instrumental samples is found in only the more expensive models. Remember that, depending on the sample rate used, samples may be more or less accurate representations of the original voice. Because manufacturers almost never reveal these sample rates, our ears must judge the relative quality of the voices of the digital piano models we’re comparing.

Note that many manufacturers have trademarked their names for a particular sampling technology or other aspect of an instrument. The important thing to remember about trademarks is that while the trademarked name is unique, the underlying technology may be essentially the same as everyone else’s. For instance, the generic term for digital sampling, discussed in Part 1, is Pulse Code Modulation, or PCM. But a manufacturer may call their PCM samples UltraHyperDynoMorphic II Sampling , and rightly claim to make the only product on the market using it. However, that makes it only a unique name, not necessarily a unique technology.

Layering and Splitting

Layering — the ability to have one key play two or more voices at the same time — is available on virtually all digital pianos. Some combinations, such as Piano and Strings, are commonly preset as a single voice selection. On many instruments, it’s possible to select the voices you’d like to combine. This is frequently as simple as pressing the selection buttons for the two voices you want to layer. Once these are selected, many instruments then allow you to control the two voices’ relative volumes. Using the popular Piano and Strings combination as an example, you may want the two voices to play with equal volume, or you may want the Piano voice to be the dominant sound, with just a hint of Strings. Other possible settings include the ability to set the apparent positions of the individual voices in the left-right stereo field — with Strings, say, predominantly on the left. The most advanced instruments make it possible to have only one voice’s dynamics respond to your touch on the keyboard, while the other voice responds to a separate volume pedal (this is described in greater detail under “Other Controls”).

The other commonly available voice option is splitting. Whereas layering provides the ability to play two voices with one key, splitting lets you play one voice on the right side of the keyboard, and a different voice on the left side — for instance, piano on the right and string bass on the left. This essentially lets the instrument behave as though it had two keyboards playing two different voices. The split point is the point in the keyboard where the right and left voices meet. While this split point has a default setting, it can also be moved to provide more playing room for one voice or the other. As with layered voices, there may be preset combinations, but you can also set up your own voice pairings; typically, additional options are available to vary relative volume levels and other settings between the two voices.

Effects

Digital effects electronically change a sound in ways the originally sampled source instrument typically could not. Effects can be loosely divided into those that mimic the acoustic properties of a performing space and those that modify the sound in non-acoustic and, in some cases, downright unnatural ways.

The most popular effect — in fact, the one most people never turn off — is Reverberation, or Reverb. The easiest way to understand reverb is to think of it as an echo. When reflective surfaces are close to the sound source and to you, the individual reflections of the original sound arrive at your ears from so many directions, and so closely spaced in time, that they merge into a single sound. But when the reflective surface is far away, there is a time lag between the original and reflected sounds that the ear recognizes as an echo, also known as “reverberant sound.” The strength and duration of the echo depends on a number of factors, among them the volume and frequency of the original sound, and the hardness and distance of the reflective surfaces. Different amounts of Reverb lend themselves better to different types of music. Although you can just leave Reverb on the default setting, you also can broaden the instrument’s tonal palette by exploring alternate settings.

The other common effect is Chorus. When a group of instruments play the same notes, the result is not simply a louder version of those notes. Even the best performers will be very slightly out of synchronization and out of tune with each other. This contributes to what’s variously referred to as a “full,” “fat,” or “lush” sound. The Chorus effect is frequently built into ensemble voices like Strings and Brass and, of course, Choir.

Before we leave the subject of effects, there is one other application to be covered here: dedicated effects speakers. Some upper-end digital pianos now come with speakers whose role is not to produce the primary sound, but to add to the apparent ambience of the instrument and the room. These speakers and their associated effects can significantly alter the sound of instrument and room. When done well, these effects are not noticed until they’re turned off, when the sound seems to “collapse” down to a smaller-sounding source.

Alternate (Historical) Tuning

One of the advantages offered by the digital piano is the fact that it never requires tuning. This does not, however, mean that it cannot be tuned. Just as we tend to think of the piano as something that has always sounded as it does today, we similarly tend to think that tuning is tuning, and has always been as it is now. In fact, our current practice of setting the A above Middle C at 440Hz, and the division of the octave into intervals of equal size for the purpose of tuning, are relatively recent developments.

Evidence suggests that international standard pitch, while a bit of a moving target depending on where, when, and for whom you were tuning, had pretty well settled down to A = 440 Hz by the mid-19th century. And by the late 19th century, following a few centuries of variation, we had arrived at the tuning system of equal temperament.

Now that all that has been settled, why bother with alternate tunings? You may never use this capability, but for many it is a profound experience to hear firsthand how the music of J.S. Bach sounded to Bach himself, and thus to realize why he wrote the way he did. Instruments that include alternate tunings list in a menu the most common historical temperaments (tuning systems). Select an appropriate temperament, adjust the pitch control, and you have a time machine with keys. It’s a simple and invaluable tool for those interested in music history, and some instruments allow you to create your own unique temperaments for the composition of experimental or modern music.

MIDI

Electronic musical instruments had been around for decades, but were unable to “talk” to each other until 1982 and the introduction of the Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) specification. Many musicians used two, three, or more synthesizers in their setups, each with a distinctive palette of sounds, to provide the widest possible range of voices. The problem was that the musicians couldn’t combine sounds from different synths and control them from a single keyboard, because of differences in the electronic commands to which each synth responded. This ultimately led to a proposal for a common set of commands to which all digital musical instruments could respond.

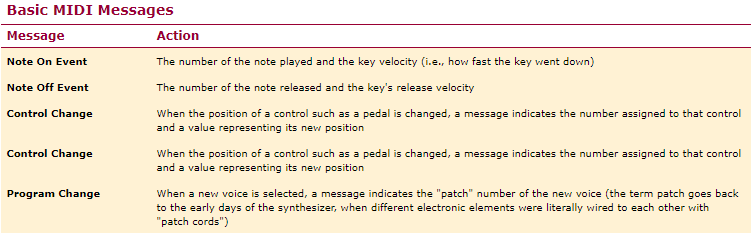

In short, MIDI is not a sound source, but a set of digital commands — or, in the language of MIDI, messages — that can control a sound source. MIDI doesn’t even refer to notes by their proper names; for example, middle C is note number 60. When you use the recording feature included in most digital pianos, what you’re actually recording is a sequence of digital messages; hence the term sequencer for a MIDI recorder (some upper-end models now allow both MIDI and audio recording). These messages form a datastream that represents the musical actions you took. Some of the most common messages are listed in the table below.

There are many more message types, but this should give you an idea of how MIDI “thinks.” Nothing is a sound — everything is a number. When recording or playing back a sequence of MIDI messages, timing — just as in a piece of music — is obviously a critical element, so MIDI uses a “synchronization clock” to control the timing of each message. MIDI can also direct different streams of messages to different channels. Each channel can be assigned to communicate with different devices; for instance, your computer and another keyboard.

While the MIDI specification of 1982 standardized commands for events such as note on, note off, control change, and program change, it didn’t include a message type for instrumental voice. It was still necessary to manually set the voice that would play on each synth because there was no consistency between instruments from different manufacturers, or sometimes even within a single manufacturer’s product line, as to which command would produce which voice. This changed with the adoption in 1991 of the General MIDI (GM) standard, updated in 1999 to General MIDI 2 (GM2).

Product specifications now frequently state that an instrument is General MIDI, or GM, compatible. Like MIDI, General MIDI specifies not a sound source but a standardized numbering scheme. Any digital instrument “thinks” of the different voices it produces not as Piano or Violin or Harpsichord, but as Program Change numbers. General MIDI established a fixed list of Program Change Numbers for 128 “melodic instruments” and 1 “drum kit.” GM2 later expanded this to 256 melodic voices and 9 drum kits. So all GM-compatible instruments use the same numbers to represent a given voice: Acoustic Grand Piano is always Program Change Number 1, Violin is always 41, and Harpsichord is always 7. A standardized numbering scheme of 256 melodic instrumental voices seems big enough to cover everything under the sun with room to spare, until you notice that some MIDI voices are actually combinations of instruments. For instance, Program Change Numbers 49 and 50 are String Ensemble 1 and 2, representing different combinations of string instruments playing in ensemble. Also, there are many Ethnic instruments (voices 105 through 112), and several Sound Effects, from chirping birds to gunshots. If this has you feeling that perhaps 256 wasn’t an unreasonably high number of voices after all, consider that many higher-end digital pianos have more than 500 voices, and some more than a thousand. This means that when you record using voices from the far end of the list on one manufacturer’s “flagship” model, then play the recording back on someone else’s top-of-the-line model, voice consistency once again flies out the window. Perhaps the most important thing to remember is that the GM standard doesn’t specify the technology used to create the listed voices. One hint of the degree of variation possible under this system is the fact that your current cell phone is probably GM compatible.

In the 1990s, two proprietary extensions to the General MIDI standard were made, by Roland and Yamaha. Roland’s GS extension was largely incorporated into the GM2 standard. Yamaha’s XG extension defines far more voices than the other schemes, but hasn’t been as widely adopted as General MIDI.

Connecting to a Computer

MIDI is now standard on all digital pianos. While it does allow your instrument to control or be controlled by other instruments, today it’s most often used to connect the instrument to a computer. Connecting your instrument to a computer allows you to venture beyond the capacity of even the most capable and feature-packed digital piano.

Connecting two instruments to each other requires two MIDI cables — one for each direction of data transmission between the two devices. Standard MIDI cables use a 5-pin DIN connector, shown here. Since personal computers don’t use 5-pin DIN connectors, connecting a keyboard to a computer requires an adapter that has the MIDI-standard DIN connector on one end, and a computer-friendly connector on the other.

In 1995, the USB standard was introduced to reduce the number of different connectors on personal computers. Subsequently, MIDI over USB has emerged as an alternative that replaces two MIDI cables with a single USB link. In addition to being a common connector on personal computers, USB’s higher transmission speed increases MIDI’s flexibility by allowing MIDI to control 32 channels instead of the 16 specified in the original MIDI standard. USB connectivity is now finding its way into the digital piano. All current digital instruments still have 5-pin DIN connectors for traditional MIDI, but many now sport USB connectors as well. One thing to be aware of is that there are two types of USB connections that can appear on instruments. One, “USB to Device,” allows direct connection to a variety of external memory-storage devices. The other, “USB to Host,” allows connection to computers. If you plan to use these connections, you need to check the type of USB connections available on the instruments you’re considering. Simply stating “USB” in the specifications doesn’t tell you the type of USB connectivity provided.

External Storage

External storage consists of any storage device that’s connected to the instrument rather than being built into it. As instruments become more advanced, they can require greater amounts of space in which to store MIDI recordings, audio recordings, additional rhythm patterns and styles, even additional sounds. Because different users need different amounts of storage, it’s becoming increasingly common for manufacturers to allow the user to attach external USB storage devices to augment onboard storage.

Floppy-disk drives were once popular in digital pianos, due to the large volume of MIDI files that were distributed using that format. These files run the gamut, from simple classical songs to complete orchestral arrangements, and even ones that use the special learning features of a particular instrument model to guide you through the process of learning a new piece of music. It’s now possible to download these files from the Internet and store them on a USB flash drive (aka thumb drive). These drives are the ultimate in handy, portable storage, and can have as much as 64GB of memory. Not only are they unobtrusive when attached to the instrument; if your digital piano and computer are in different rooms, a flash drive can make file transfers quick and painless.

Some instruments give you the ability to play and record digital audio using a USB flash drive. These recordings are saved as uncompressed .WAV files, typically at the same bit depth (16) and sampling rate (44.1kHz), though not the same file format, used for commercial audio CDs: one five-minute song can consume up to 50MB of memory. Some instruments provide the option of recording your audio in the popular MP3 format, which can now offer good sound quality, and can be more convenient for listening and sending via e-mail. Either format can easily be transferred to a computer’s hard drive, or a portable hard drive, for permanent storage.

Computer Software

As mentioned briefly in the discussion of MIDI, perhaps the most powerful option that accompanies the digital piano is the ability to connect your instrument to your personal computer and enhance your musical experience by using different types of music software. Software can expand capabilities your instrument may already have, such as recording and education, or it could add elements like music notation and additional voices. While it’s beyond the scope of this article to describe music-software offerings in detail, we’ll take a quick look here at the different categories: Recording and Sequencing, Virtual Instruments, Notation, and Educational.

Recording can take two forms on the digital piano: data and sound. All models that offer onboard recording (i.e., nearly all of them) record MIDI data. This means that all of the actions you take when you play a piece — both key presses and control actions — can be recorded by a MIDI sequencer. But remember that a MIDI sequence, or recording, is data, not sound. Recording the actual sound of your music is a different issue, and few digital pianos can do this.

Enter recording software. Recording software ranges from basic packages — even the most modest of which will exceed the recording capabilities of most digital pianos — to applications that can handle complete movie scores, including film synchronization. The higher-end applications are called Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs). These software applications cost more than many of the lower-priced digital pianos, and can be used to record, edit, and mix combinations of MIDI and audio tracks, limited only by the processing power and storage capacity of the computer. If you have an opportunity to look inside a modern recording studio, you’ll find that computers running DAW software have replaced multi-track tape recorders.

Virtual instrument software can be controlled, or “played,” by your digital piano via MIDI, and can also be played by recording software that resides on the computer. Virtual instruments can take the form of standalone software or plug-ins. Standalone instrumental software doesn’t rely on other software, but plug-ins require a host application such as the DAW software described above, or other software developed specifically as a plug-in host. Virtual instruments can be sample sets for strings, horns, or even pianos, or they can accurately emulate the sonic textures and controls of popular electronic instruments that are no longer produced, such as certain legacy synthesizers. (A number of piano-specific virtual instruments are explored in the article “My Other Piano is a Computer,” elsewhere in this issue.) While virtual instruments allow you to expand your sound palette beyond the onboard voices of your digital piano, they can place heavy demands on your computer’s processor and memory. A mismatch of software demand and hardware capability can result in latency — audible delay between the time the key is played and the time the sound is heard. If both the digital piano’s onboard voices and the virtual instrument’s sounds are played simultaneously, there could be a time gap between the two outputs that would make the result unusable. Virtual instruments can be an exciting addition, but be prepared for the technical implications.

Notation applications are the word processors of music. If you have a tune in your head and want to share it, simply recording it will allow others to hear it. But in order for most people to play your music, it must be written out in standard notation. In the early days of notation software, it was necessary to place each note on the staff individually using the computer’s keyboard and mouse. The advent of MIDI created the ability to play a note on a musical keyboard and have it appear on the computer screen. Today’s notation programs virtually take musical dictation: you play it, and it appears on the screen.

But there’s a slight hitch that must be addressed. The computer’s capacity to accurately capture the timing of your playing, down to tiny fractions of a second, allows it to reproduce subtle nuances with great precision. In a recording, this is a great asset; in notation, it can be a complete disaster. If — in the computer’s cold calculations — you’ve just played a passage involving dotted 128th-note triplets, the software will happily display them. Unless notation applications are told otherwise, they are perfectly capable of creating notation that is absolutely accurate and absolutely unreadable. This is where quantization comes in. Quantization — also applicable to the recording capabilities of higher-end digital pianos — allows you to specify, as a note value, the level of timing detail you desire. If the software is told to quantize at the eighth-note level, the printed music will contain no 16th notes — nothing shorter than an eighth note will be scored. If quantization is set at 16th notes, there will be more detail; if set to quarter notes, the music will be devoid of any timing detail beyond that value. This must be used judiciously; too much quantization and musical detail is lost, too little and the notation becomes an indecipherable pile of notes (for a good laugh, Google “Prelude and The Last Hope in C and C# Minor”). As with recording applications, there is a wide range of capabilities available, from programs that will let you capture simple melodies, to applications that will easily ingest the most complex symphonic works, transpose and separate the individual instrumental parts, and print them out.

The final category we’ll discuss is educational software. Just as there are educational programs and games to assist in learning math or reading, there are applications that use the MIDI connection between your instrument and computer to help you learn different aspects of music. A music-reading program may display a note, chord, or passage on the screen; you play the displayed notes on the digital piano and the software keeps track of your accuracy and helps you improve. An ear-training application may play for you an interval that you then try to play yourself on the keyboard. The application will tell you what you did right or wrong and help you improve your ear. Other types teach music history and music theory. While many of these applications are geared to specific levels or ages, some can be set to multiple levels as you progress, or for use by multiple players.

Onboard Recording

Recording has been discussed above, in the “Computer Software” section. However, because nearly all digital pianos come with at least basic recording capability, it deserves a bit more attention. You may say that you have no intention of recording your music for others to hear, but in ignoring the instrument’s ability to record what you’ve played, you may be overlooking one of the simplest ways of improving your playing. Whether you’re just starting to play or are beginning to learn a new piece, being able to hear what you’ve just played is a learning accelerator.

I know what you’re thinking: “I heard it while I was playing it.” While most professional musicians have reached a level where they can effectively split their attention between the physical act of playing the instrument and the mental act of critically listening to what they’re playing, few of the rest of us can do this. Recording and listening to yourself will reveal elements of your playing that you never noticed while you were playing, and will allow you to see where to make changes in your performance. This is even more useful when working with a teacher. Imagine listening with your teacher, music score in hand, and pausing the playback to discuss what you did in a particular measure. This is one of many reasons piano teachers are adding digital pianos to their studios; they’re great learning tools.

One final thought on recording on the digital piano: Most manufacturers list recording capacity as a certain number of notes — typically in the thousands of notes. But not everyone is counting on the same number of fingers. Recall that MIDI records data “events,” including note on, note velocity, note off, program change, control change, and a variety of others, many or all of which could have happened in conjunction with the playing of a single note. Each of these events consumes a certain amount of internal memory. Because this memory capacity is fixed, unless we know which events each manufacturer is counting as “notes,” it’s pointless to try to decide, based on these specifications, who offers more recording capacity. On the one hand, most instruments have more recording capacity than most owners will use. On the other hand, if recording capacity is important to you, this is another of the many areas in which simply buying the biggest numbers, or the most numbers for the dollar, is not a good strategy for selecting an instrument.

Automated Accompaniments, Chords, and Harmony — the Ensemble Piano

Some people, even some professional musicians, will tell you that using automated accompaniments — those rhythmic combinations of drums, bass lines, and chords — constitutes “cheating.” This has never made sense to me. If I use a tool to do something that I couldn’t possibly have done with my bare hands, am I cheating?

Whether or not a digital piano has these automatic features, frequently referred to as styles, is the primary factor that separates standard digital pianos from ensemble pianos. If your musical interest is focused solely on the classical piano repertoire, then this capability will probably be of no interest to you. If, however, you or someone in your household plays or plans to play a wide variety of musical styles, the ability to have backup instrumentalists at your beck and call is just entirely too much fun. No matter how good a player you may be, you can’t be four people at once — or eight, or twelve, or an entire orchestra. These accompaniments are typically divided into groups by musical genre: Swing, Latin, Rock, World, and so on. The best of these styles are of a caliber that the best record producers would be proud of.

One thing to watch out for is the impact of automatic accompaniments on polyphony (see Part 1). Every bass line, drum beat, string sound, and guitar strum takes a toll on the number of simultaneous notes the instrument can produce. Thirty-two notes of polyphony can get used up in a big hurry when a complex style is playing in the background. If styles are important to you, look for higher polyphony numbers. Also, see if the instrument you’re considering is capable of downloading additional styles, and how many styles are available for that model.

How do these styles “know” which key to use when playing all those chords and bass lines? In the simplest “single finger” settings, if the player needs an accompaniment style played in C, for example, she plays a C with the left hand. As chords change in the music, the player makes the appropriate change in the left hand to indicate what the accompaniment should play. Once the harmonies have been determined, the instrument can also apply them to the right hand by filling in the notes of the appropriate chord under the melody note. More sophisticated systems can decipher complex chords by evaluating all of the notes played on the keyboard, so that even advanced players can use the accompaniment styles without being held back from their normal style of playing.

All of this technology can make raw beginners sound as if they’ve been playing for years. While many players will progress beyond the simplest settings, other members of the family may continue using these playing aids for their own enjoyment.

Memory Presets

With the huge variety of voices, splits, layers, effects, and styles, it’s handy to have a way to store favorite combinations. Many digital pianos come with a number of preprogrammed presets, and almost all of the more advanced models have programmable presets as well. These presets should be able to capture every possible setting on the instrument, from the obvious to the most obscure. Aside from the number of presets available, the placement of the preset buttons themselves can make a huge difference in their usefulness. Small, closely spaced, inconveniently placed presets might as well not be there — part of the pleasure of presets is not simply to instantly recall a setting that you’ve worked out in excruciating detail, but also to access that setting quickly and easily while playing. Even better is being able to assign preset changes to a seldom-used pedal (anything other than the sustain), so that each time you press the pedal, the instrument advances to the next preset. This can enable the creative player to step through sonic and rhythmic changes with ease while keeping his hands on the keyboard and distractions to a minimum.

Song Settings, Music Libraries, and Educational Tools

Many digital pianos are equipped with a list of song presets, a feature that goes by a variety of names depending on the brand of instrument. Like the memory presets described above, song presets incorporate all of the capabilities of that particular digital piano, but they work with particular songs. When you’re new to the vast choices offered by some of the more advanced digital pianos, and unsure what sounds and styles to use for a song, these presets will set everything for you in a way suited to that song. Of course, this depends on the song you want to play being included in that instrument’s song list in the first place. These lists range from a hundred or so built-in songs to downloadable databases containing thousands of songs, and the best of them accurately reflect the instrumentation, rhythms, and tempo (which you can slow down or speed up if necessary) of the original recordings. It’s important to note that these song presets don’t play the music for you; they just set up the instrument so that it will sound right when you play the music.

A related feature, but with a different purpose, is the song library. Once again, this feature goes by different names depending on the instrument’s brand. Unlike the song presets, the song libraries do contain the actual music. In most cases these are from the classical piano repertoire and are recorded with the left- and right-hand part s on separate MIDI channels. They can be played with both hands turned on for listening or studying, or with only one hand turned on so the player can practice one hand’s part while the instrument supplies the part for the other hand. In this way each part can be worked on separately, while both parts are heard. Although the tempo can be adjusted (for most of us, slowed way down), playing along with the other part keeps your tempo steady and your meter honest. Even without built-in libraries, an enormous amount of music has been recorded in this manner and can be purchased — frequently with the printed notation — or downloaded free from the Internet.

Combinations of song libraries and computer-based educational software can be found on both entry-level and top-end instruments. These range from simple separation of left-hand/right-hand practice to complete lessons, tests, and tips on fingering. Some of the greatest aids to beginners are systems that combine the display of notation with visual cues as to which keys to play. Upper-end models use either lights aligned with each key, or movement of the key itself, to give the beginner a hand in correctly associating the note on the printed music with its key on the instrument. However, seeing which key to play, and actually playing it before the music has moved on, are two different things, and trying to do so can be a frustrating experience. Some instruments make it easier to follow the light or key movements by waiting until the correct key is played before moving on to the next key. As a less expensive alternative, some lower-priced instruments show a small keyboard on the display with the required key indicated. While this still provides some guidance for the beginner, it’s not nearly as easy to associate movements between the tiny keys in the display with the correct keys on the keyboard.

Other Controls

The ability to connect an accessory volume pedal is fairly common on upper-end and professional digital pianos. While the thought of a volume pedal attached to a piano may at first seem odd, it can actually add some interesting possibilities. Although it can be used to control the volume of the entire instrument, some models will allow you to select which aspects of the instrument are controlled by the pedal. One of my favorite ways to use the volume pedal is to layer an orchestral string voice with the piano voice and have the volume pedal control only the strings. This allows me to fade the strings in and out while the piano remains within its normal dynamic range.

While we’re on the subject of pedals, it’s worth noting that many instruments allow you to assign different functions to the standard piano pedals. As with the addition of the volume pedal above, this may initially strike you as a strange thing to do, but the presence of the non-piano voices can make sense of the situation. Some of the most common and handiest examples of alternate functions for the less-used sostenuto and soft pedals are pitch bend, rotary-speaker speed control, and triggering rhythm breaks.

Pitch bend, as the name suggests, allows you to temporarily raise or lower the pitch of a note, then allow the note to slide back to its normal pitch. The most common setting is to have a pedal set to lower the pitch of a note by a half step (the very next note below), then allow the pitch to slide back up to normal when the pedal is released. Think of the opening clarinet line in Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue — the trill leads to an ascending scale, and the player slides to the last note at the top of the scale. This effect is duplicated by depressing the pedal (set for pitch bend) and playing the upper note of the slide at the time you would have played the lower note. The pitch bend will cause the key for the upper note to instead play the lower note; then lift the pedal and you’ll slide from the lower note to the upper one. It requires some practice, but isn’t as difficult as it sounds.

Setting a pedal for rotary-speaker speed control allows the digital piano player to duplicate the effect produced by the rotating baffle and horns of the classic Leslie speaker, typically used with “drawbar” or “jazz” organ sounds. One of the techniques used by players of this type of organ is switching between the slow Chorus rotation of the speaker and the fast Tremolo rotation. As this is done while playing, being able to tap a pedal to switch speeds makes the effect much easier to use.

One of the easiest and most useful pedal assignments is to trigger a rhythm break. The break is a brief variation in the rhythm or style in use at the time. Once again, the ability to activate a feature without taking your hands off the keyboard makes use of that feature much more spontaneous.

Special controls usually found only on professional stage pianos are the pitch bend and modulation wheels. The pitch-bend wheel acts in the same way as the pitch bend described above, but with a dedicated control instead of a pedal. A number of different effects can be assigned to a modulation wheel, depending on the voice in use or the player’s choice. The most common default setting is vibrato, a repeating pattern of up-and-down pitch variation around a note, such as the wavering sound in a singer’s voice. The modulation wheel allows the player to control the amount of vibrato in real time while playing. This is particularly useful in creating additional realism with solo instrumental voices such as Saxophone, Violin, and Guitar.

Vocals

Many who love to play also love to sing, and the digital piano has something for vocalists as well. Many instruments now feature a microphone connection. In its most elementary form, this simply uses the digital piano’s audio system as a PA for vocals. But some models throw the full weight of their considerable processing power behind the vocalist. Many vocal recordings and performances take advantage of effects processing to enhance the performer’s voice. This can range from adding reverberation to effects that completely alter the performer’s voice, making it sound like anything from Barry White to Betty Boop. Top-of-the-line digital pianos can even go beyond what some recording studios can do. Perhaps even more amazing is the ability of some instruments to combine the vocal input with their ability to harmonize, resulting in your voice coming out in four-part harmony. Display of karaoke lyrics is also common; the presence of a video output on some instruments allows the lyrics to be displayed on a TV or other monitor.

Moving Keys

When an acoustic player piano plays, the keys must move in order for the hammers to strike the strings and produce sound. The digital piano does not share this mechanical necessity, yet we now have digital pianos whose keys move when playing a recording. You’ll recall from the section on recording that the digital piano can record and reproduce your playing, or can reproduce a MIDI file from another source. The sounds are produced by sending the playback data directly to the tone-production portion of the instrument, bypassing the keyboard. But since there is no dependency on moving keys, why go to the extra expense of making them move? Two reasons: First, it’s one way for the instrument to direct beginners to the next melody note in the educational modes of some models, as described earlier under “Educational Tools.” Second, it’s just fun to watch. However, you should measure the value of this feature against the additional cost, and be mindful of the increased possibility of mechanical failure due to the additional moving parts of the key-drive mechanism.

Human Interface Design

The Man-Machine Interface, or MMI, as designers and engineers typically refer to it, defines how the player interacts with the instrument’s controls. All of the amazing capabilities of the modern digital piano are of little value if the player can’t figure out how to use them, or can’t access them quickly while playing. The considerations here are the location, spacing, grouping, size, shape, colors, and labeling of the controls. Take the example of the rhythm break discussed earlier. Its purpose is to alter the rhythm during playing. If the button that activates this feature is inconveniently located, small, and surrounded by closely spaced buttons of a similar size, shape, and/or color, its usefulness is severely limited. If, however, it’s within easy reach of the keyboard, of decent size, and somewhat distinctive in appearance or markings, it becomes a useful tool.

In the case of instruments with displays, considerations include the size, resolution, and color capabilities of the screen and — more important — the logic behind its operation. Two types of screen interfaces are currently used on digital pianos: touchscreens and softkeys. Most readers are already familiar with touchscreens from ATMs and other modern institutional uses. The term softkeys doesn’t refer to the feel of the keys, but to the fact that their functions are displayed on the adjacent screen, and change depending on the operation being displayed by the screen. This is as opposed to hardkeys, which have a single dedicated function. Each method has its proponents, but the interface type is less important than the MMI design. A smaller monochrome display that you can intuitively understand is better than a large color display that makes no sense to you.

Also worth considering is the placement of connections you’ll use often. If you frequently switch back and forth between speakers and headphones, you’ll want to make sure the headphone jack is easy to locate by sight or feel, and that the cord will be out of your way when plugged in. If you’ll be using a USB memory device to transfer files between instruments or between the instrument and a computer, make sure the USB port is easy to get to. In newer designs, a USB port is placed above the keyboard level for easy access, as opposed to earlier models in which the port was below the keyboard or on the instrument’s rear panel.

We can’t leave the subject of user interfaces without discussing the owner’s manual. As with the MMI itself, a well-written manual can make it a pleasure to learn a new instrument, and a bad manual can be worse than useless. This is particularly important for higher-end instruments. Fortunately, many manufacturers allow you to download the manuals for their instruments. This lets you compare this critical aspect of the instruments you’re considering. The manual should be thoroughly indexed, and clearly written and illustrated. Third-party tutorials are available for some instruments, especially the more complex models. These tutorials step you through the model’s functions with audio or video instructions, and provide an alternative to sitting down with the manual.

Firmware Upgrades

The digital piano is, at heart, a highly specialized computer, and like all computers, its functions are dependent on its software. When we speak of the software that runs on the digital piano, we are typically talking about what is properly classified as firmware. Firmware is software that is embedded in a hardware device such as a microprocessor or associated memory chip. This can be done in two ways: the firmware can either be permanently burned into the chip, or it can be written in the chip’s memory, which also means it can be rewritten if necessary. Just as computers occasionally need a software upgrade to fix a previously undetected problem — a “bug patch” — the more complex digital pianos can benefit from the ability to accept firmware upgrades. This may never be necessary for a given model, or it may fix an obscure feature interaction or update the instrument’s compatibility with external devices. In addition to checking on this capability, it’s worth finding out how you would be notified of an update and what the actual update procedure involves. In most cases today, it’s an easy, do-it-yourself procedure.

Headphones

Headphones are by far the most popular and frequently used digital-piano accessories. One of the advantages of digital pianos is the option to practice without disturbing others — or them disturbing you. Whether you’re an occasional headphone user, or your instrument or situation dictates constant headphone use, selecting the right headphones will make a big difference in your playing comfort and enjoyment.

When I select headphones, I evaluate them using four criteria: fit, sound, isolation, and budget. Although it may seem that starting with sound is the obvious choice, my first priority is fit — it doesn’t matter how great they sound if you can’t stand to wear them for more than a few minutes. There are three basic styles of headphones: those that fit around the ear (circumaural) with the cushions resting on your head, those that rest directly on the ear, and those that fit in the ear. The style of headphone you choose will also determine the level of isolation. If isolation is critical for your situation, it should dictate the style of headphones.

There are a couple of variations on the circumaural and in-ear styles. Circumaural headphones can be open or sealed. Open designs don’t cut you off from the outside world, and their output can be heard — very softly — by anyone nearby. Sealed designs offer more isolation but introduce some acoustic design problems that are difficult to get around until you get into the higher price ranges. In-ear headphones are available in the earbud style that sits in the outer ear, and the ear-canal type that fits inside the ear canal itself. The latter offers, by far, the best isolation in both directions, even when compared to headphones with active noise canceling.

Sound is very much a matter of personal preference and perception. One thing that can make the selection process easier is to bring a familiar CD with you when you audition headphones. While you may initially favor headphones that color the sound in some attractive way, this can become sonically tiring with extended listening. If you aim for a neutral sound, you’ll end up with headphones that won’t tire your ears over extended periods, and that will most accurately represent the sound produced by your digital piano or by the models you’re considering.