With pianos as with cars, older is not necessarily better. Even when well maintained, pianos, like all musical instruments, can eventually wear out from natural aging and heavy use. If they are to continue to function, they may need highly specialized restoration, with replacement parts that can be hard to find or reproduce. Also, really early pianos, those with all-wood construction and low-tension scaling, were not designed for modern conditions, whether environmental (e.g., central heating), musical (Elton John), or both (a solo recital under hot lights in a large concert hall).

But like any fine antique, a well-preserved old piano can have a value beyond everyday practical use: as a status symbol; as a piece of period furniture, often elegant and unique; as tangible evidence illustrating a phase of music history or a technical innovation; as a link connecting generations through stories of ownership (Great-grandma’s piano carried West in a covered wagon); or as an encyclopedia of information about age-old crafts, manufacturing methods, and design principles. These are among the reasons that leading museums—such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Art Institute of Chicago—display historical pianos, and why scholars study and write about them.

Most important for musicians and listeners, however, pianos of earlier times can reveal how Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Liszt, Brahms, and other 18th- and 19th-century pianist-composers expected their compositions to sound: quite different from when played on high-powered, comparatively standardized modern grands, with their richer, more sustaining tone but relatively limited tonal palette. This is not to say that today’s pianos are inadequate or inferior, but their qualities of tone, touch, and articulation differ markedly from the lighter, more delicate, crisper sounds of earlier pianos—just as the characteristics of jumbo jets differ from those of small, more maneuverable propeller planes used for crop dusting. Each has advantages in serving the purposes for which it was originally intended.

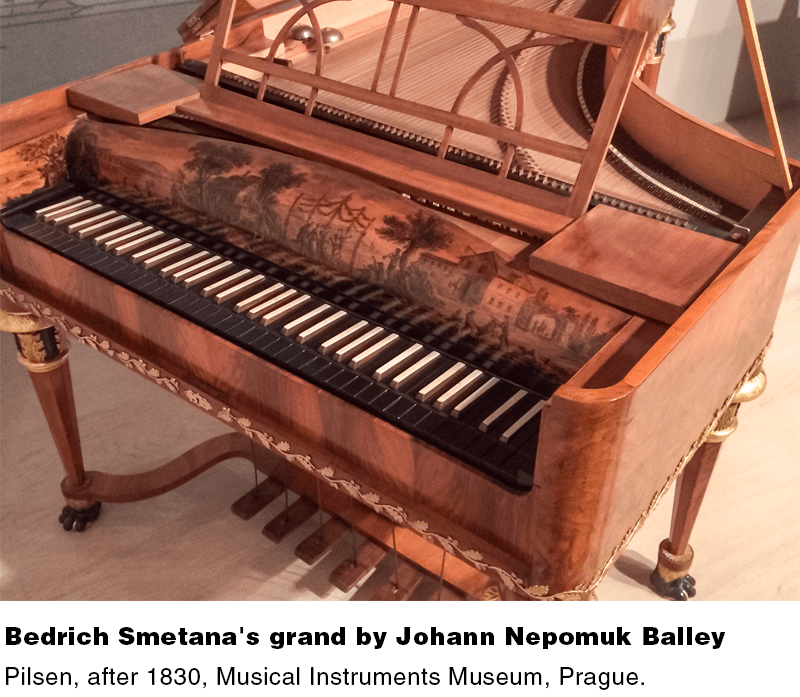

For example, Viennese-style pianos of the Classical era often came equipped with a moderator, a strip of soft material that could be quickly interposed between their hard, leather-covered hammers and their strings to dramatically change the tone color. Another curious tonal device was the bassoon stop, a roll of parchment or stiff paper lowered onto the bass strings to create a buzzing timbre. Some Classical-era grands had a divided damper rack, allowing the bass or treble dampers to be raised and lowered independently, as well as all together as in modern pianos. Also, contemporary English grand pianos commonly had “inefficient” dampers, deliberately designed to silence the strings gradually rather than suddenly, allowing sound to linger briefly after the dampers fall. Some 18th-century pianos lack dampers altogether, causing changing harmonies to blur together; Beethoven had this damperless effect in mind for the opening of his “Moonlight” sonata. Modern pianos cannot easily mimic these special effects, and lack the tonal variety of pianos from the pre-industrial past, when regional styles of piano-making offered options that stimulated musical creativity.

No doubt Mozart and Beethoven would have been amazed by a Steinway concert grand and would have taken full advantage of its capabilities once they came to grips with it; but then they would have written a different kind of music—surely using the whole pitch and dynamic range of the modern keyboard, but likely also missing the bass clarity and marked change of timbre from bass to treble that were hallmarks of their own pianos, unlike the more homogenized tone of today’s instruments. Interestingly, some historically informed piano builders today, such as Paul McNulty and Chris Maene, aim to recapture the wider tonal spectrum of straight-strung, Romantic-era and earlier instruments of varying styles of tonal design and manufacture, each perfectly suited to a particular repertoire.

So a fine old piano, or a careful replica of one, can produce nuances of articulation, shades of color, and subtleties of texture that bring familiar music to new life in unexpected ways. Of course, early models aren’t well suited to much later music; they’re limited in loudness and range of notes (61 keys, or five octaves, was normal in Mozart’s day), and may have hand stops or knee levers instead of pedals to operate the dampers and other tonal devices. Pianists unused to the lighter touch and fleet response of a Classical-era instrument may find it difficult to control at first, but as with any unfamiliar technique, practice makes perfect. Increasingly, adventurous pianists are turning to these older models to give their interpretations greater authenticity, by playing masterworks of the past on the kinds of instruments for which they were composed.

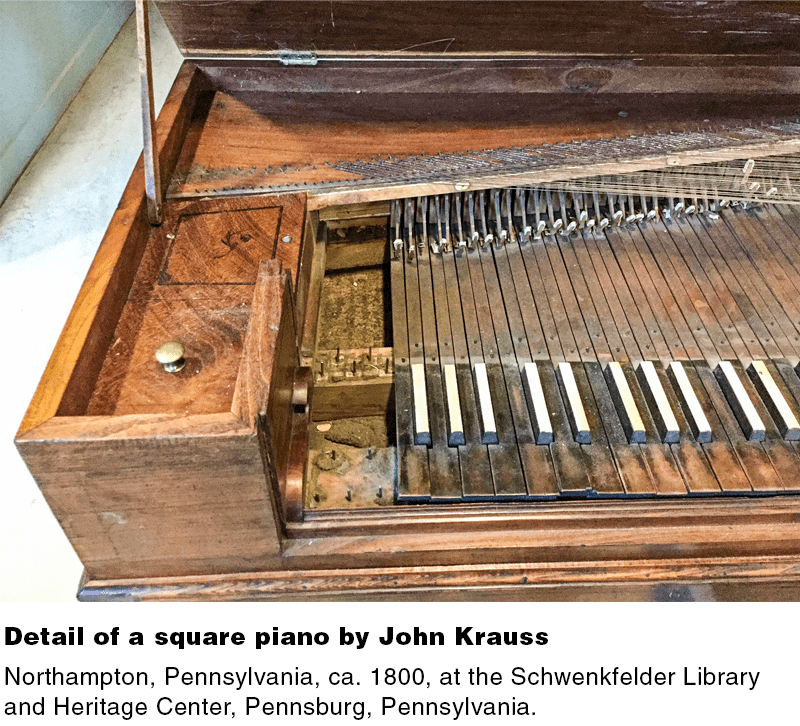

Unfortunately, piano technicians today, except those working in museums and collections of historical instruments, have limited opportunities to learn about the materials and mechanisms of pre-modern pianos. For example, low-tension iron and brass strings, and smooth tuning pins without holes for insertion of the becket, need special handling; similarly, voicing leather-covered hammers and regulating unfamiliar actions require particular training and tools. Lack of experience and difficulty finding or making replacement parts often leads technicians to denigrate types of pianos they’re unaccustomed to. This is especially true for massive, mid-19th-century “square” models, which present peculiar challenges due to their complex designs and layouts, which can make them awkward to adjust and maintain without the proper equipment. Nevertheless, the best of these thoughtfully developed squares, by leading American manufacturers such as Chickering, Mathushek, Steinway, and Weber, were highly regarded by professional performers of their day, and deserve to be approached sympathetically rather than casually dismissed as untunable. Among other admirable qualities, their precise handcraftsmanship and costly materials—fine-grained, aged spruce, rare tropical hardwoods, excellent ivory—are superior to what is ordinarily encountered today. Even for the most expensive modern pianos, ivory and some endangered hardwoods are now almost impossible to obtain legally. At the very least, unrestorable old pianos can be sources of valuable recyclable materials, including unusual hardware and action parts.

It’s important to recognize, though, that in the past, cheap, poor-quality pianos abounded, just as they do nowadays. So what distinguishes a fine antique piano, one worth preserving and possibly restoring, from a run-of-the-mill product of little musical interest when new and even less today, when it has likely deteriorated past the point of cost-effective repairs? Leaving aside cherished family heirlooms that deserve respect for sentimental reasons regardless of their condition, how can we assess an old piano’s value, potential usefulness, and historical significance? What sources of information are available?

A Valuable Antique—or Just Old?

First of all, any piano surviving from before the mid-19th century, in any condition, deserves a close look simply because it might contain irreplaceable historical data, such as journeymen’s names inscribed inside, or dates that can be correlated with serial numbers. Before any old piano is recycled or discarded, its inscriptions, labels, patent numbers, and other makers’ marks should be documented, preferably photographically, for inclusion in researchers’ databases. The most comprehensive online database, recording extant pianos by known makers from before about 1860, is “Clinkscale Online,” found at earlypianos.org. This growing resource, searchable by maker, place, model (grand, square, upright), and other fields, should be consulted and supplemented whenever possible; it can provide helpful context and comparable examples as well as extensive references. Individual manufacturer databases are also in preparation, as are Facebook pages and websites devoted to particular firms, such as Érard and Broadwood. All these sites welcome reliable information that amplifies what is known about old-time piano manufacturing.

But in the absence of a date or other clues to a mystery piano’s origin, what should someone look for in determining its potential significance?

Keyboard range: Fewer than 85 keys, or a lowest note higher than today’s lowest A, may signal an antique (disregarding later portable pianos with short compasses); and a six- or six-and-a-half-octave keyboard, or less, usually beginning on C or F, should raise eyebrows, especially if the naturals and accidentals have reversed colors (black or dark naturals, white or light-colored accidentals) as 18th-century keyboards often do.

Interior reinforcement: All-wood construction, or a partial plate only for the hitchpins, or just some longitudinal metal bars over the soundboard rather than a full cast-iron frame, usually indicates age.

Stringing: Early pianos commonly have bichord stringing throughout the compass, or trichords only in the high treble, and no single strings in the bass.

Case style: A handsome case of any period can be intrinsically valuable as furniture; its style, especially of the legs and music desk, can help date a piano by reference to museum and auction catalogues, online image libraries, and relevant websites. The American Musical Instrument Society, or AMIS (amis.org), includes museum curators, private collectors, and keyboard scholars who will happily answer questions, as will certain Piano Technicians Guild (PTG) members whose expertise extends to pre-modern instruments.

Once a piano has been found worthy of further investigation, its condition must be ascertained. Along with rarity, what chiefly determines an antique’s worth is condition. Normal wear and tear—deteriorated felts and fabrics, slightly dished and discolored ivories, abraded pedals, and minor case damage—is to be expected and, if necessary, can be corrected if original parts are saved and correct replacements are used. Past restringing, repinning, and refinishing can be hard to detect if they were properly done, and needn’t devalue a working instrument. But complete rebuilding involving wholesale replacement of original parts, causing loss of historical information, will diminish a piano’s value to a researcher, if not necessarily to a player. Certain kinds of damage, though, can be fatal, or at least far more costly to correct than an ordinary old piano is worth. Beware of a water-damaged, delaminated case, separated joints, a badly cracked pinblock, a broken iron frame, a depressed and/or badly split soundboard, loose ribs, a cracked or separated bridge, a vandalized or warped action, extensive rust and corrosion, mold, woodworm, rodent debris, and signs of previous poor repairs.

However, an 18th- or early-19th-century piano in any condition is worth careful examination before any decision is made about discarding or rebuilding it. Regarding documentation protocols, ask the advice of a competent museum curator or conservator of musical instruments, or an experienced collector. Most keyboard curators and collectors in the United States and many from abroad are AMIS members.

Surprisingly, grand pianos are not always more valuable than squares and uprights; a well-built, well-preserved square or upright in an attractive case can easily outshine a beat-up grand by an inferior manufacturer. Questions of value must be framed by asking: Value to whom, and for what purpose? Naturally, a performer will have different requirements from an interior decorator looking for a showpiece to furnish a historic home. As mentioned above, rarity is also a determining factor, and this goes beyond the mere quantity of surviving examples of a given type. For example, Clementi squares are fairly common, especially in the United Kingdom, and are valued accordingly; but only one Clementi-model square made in Mexico is known to have survived, which makes that unique, signed and dated example of immense historical importance. Likewise, playable English grands from the first half of the 19th century are not particularly scarce, but pre-1850 American grands by any maker, in any condition, are almost unknown and therefore extremely important in illustrating the run-up to Steinway. So rapid was the pace of American piano innovation before the Civil War that almost any antebellum survivor might exemplify an invention or patent of which no example is currently known.

Many factors thus separate ordinary, worn-out old pianos from potentially valuable antiques that can often lead second lives either in performance or as objects of study. Each instrument deserves evaluation on its own terms by someone who knows what to look for and how to diagnose problems that might occur. As in medicine, it is vital not to exceed one’s competence; rather, seek advice when in doubt, or when confronted by a strange situation. Most pianists and piano owners have only vague ideas of how their instruments operate, and depend on professional technicians the way car owners depend on reliable mechanics. It isn’t enough to determine that a particular instrument is interesting, or possibly precious; owners need to know how to protect fragile old pianos from biodeterioration, fluctuating climate conditions, abusive playing, misguided repairs, and other threats. Continual learning through practical experience is key to broadening one’s perceptions and range of skills, and is applicable to pianos of all ages.