For a few days each year, Frankfurt welcomes the Who's Who of the piano world, led every other year by the big German brands: Blüthner, August Förster, Grotrian-Steinweg, Schimmel, Seiler, Wilhelm Steinberg, Steingraeber & Söhne, and more. It's heaven for piano lovers, but also hell: so close to the world's greatest pianos, yet so far. The unholy din makes it hard to hear anything you play — like offering an art lover a blindfolded tour of the Louvre.

After one quick circuit, I have my bearings. The main aisle running through the center of the hall appears to be a Continental — and a cultural — divide. To the right are the German pianos and other Europeans: Italy's Fazioli and the Czech Republic's Petrof (Austria's Bösendorfer was with its owner, Yamaha, in a different hall). Everything to the left of the main aisle is from Asia, mainly Chinese companies with odd names like Otto Meister, Beijing, and Nanjing Schumann.

Dramatic Changes

But the Musikmesse's demarcation line is deceptive in this age of globalization, when the world of pianos has never been more muddled. To be sure, the annals of the piano industry are filled with firms that grew, thrived, and died. Change is normal, and consolidation is nothing new. But Germany, arguably the instrument's spiritual home, is now undergoing one of the most dramatic changes in its nearly 300-year history of making pianos. In April 2015, Braunschweig piano builder Grotrian-Steinweg announced that it had sold a two-thirds stake in its company to Parsons Music, of Hong Kong — which, only two years earlier, had purchased the Wilhelm Steinberg company. In January of this year, Braunschweig's Schimmel family sold a 90% stake in its company to China's state-owned Pearl River Piano Group. In less than a year, two leading German piano families — with 311 years of piano history between them — have sold to Chinese buyers.

For Schimmel, the Pearl River takeover ends years of financial struggle. Company president Hannes Schimmel-Vogel says the deal was a difficult decision, but the only sensible path left. "Either we could stay independent, things would get ever more difficult, and eventually we'd become another dead German brand — or we could decide on a path that has a future," he said. "There are concerns, of course, about the deal and the future path of the company. But we will invest here to make sure that ‘Made in Germany' quality has a future."

In German piano circles, few topics divide opinion so strongly as the arrival of the Chinese. By selling out to China, are German piano families securing their firms' futures, as some believe, or are they digging their industry's grave? It's an emotional debate — not surprising, given the piano's contribution to the cultural heritage of its home continent, and to Germany in particular. But it's a sign of the times that, in the mainstream German media, the Chinese shopping spree has attracted little attention. A Chinese takeover of German auto makers would be a bombshell. But who cares about German piano firms?

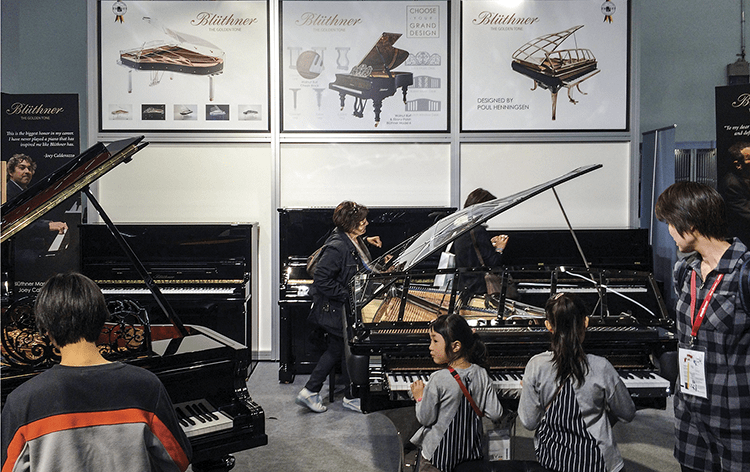

In the Musikmesse piano hall, few seem concerned about — or even aware of — the changes afoot. Hour after hour, the hall attracts scores of professional and hobby pianists, anxious to show off on concert grands they can't hear, let alone afford. Look closer at the crowd, though, and you'll see a steady stream of trade visitors heading to the far left corner of the hall and the stand of Pearl River. The Guangzhou-based company is now the world's No.1 producer of pianos, turning out 130,000 grands and uprights annually under various brand names of its own, as well as entry- and mid-level pianos under contract with Western companies. Given that scale, the 2,500-instrument output of its new Schimmel subsidiary is a drop in a very big bucket.

But Pearl River says its acquisition of Schimmel is about quality, not quantity. June Wang, manager of Pearl River's foreign-trade department, says that the takeover — which both sides insist on calling a partnership — will work only if there is benefit for West and East. "We will not change Schimmel in Europe," she says. "We are investing, and we will not build Schimmel pianos in China. We will give them financial support; they have enough technical ability and a very good reputation."

Ask dispassionate observers of the piano market what's going on, and they say that the rise of China is simply the latest chapter of a story that began with the arrival of Japanese pianos in the U.S. and Europe in the 1960s and '70s, and continued in the 1980s with pianos from Korea. In that saga, the lower-priced imports, quickly improving in quality, put the weaker Western companies out of business. Most agree that, as with the other Asian countries before them, both the quality and the quantity of Chinese pianos are rising exponentially.

Those who run the Chinese companies have also changed focus. The short-term opportunists of the past have given way to a new generation of assiduous Chinese owners, determined to capitalize on globalization trends. And on cultural shifts: European children are more likely to play Minecraft than Mozart, whereas some 80 million children in China are taking piano lessons. Call it the Lang Lang effect, after the charismatic Chinese concert pianist, but owning a high-end European instrument has become an important status symbol for China's growing middle class. And so, the market reality in 2016 is this: Container ships leave Asia piled high with low-cost pianos for cost-conscious U.S. and European markets; on their return journeys, the ships carry high-end European pianos to Chinese customers.

According to Burkhard Stein, chief executive of Grotrian-Steinweg, his firm's controlling family decided that the sale to Parsons was the best way to secure the company's future before, as with Schimmel, the situation became critical. Since March, Grotrian-Steinweg instruments have been sold through the Parsons dealership network in China — 100 Parsons shops and 400 partners — and the Braunschweig firm is already feeling the benefits. "We have an increased production capacity and, in the second half of this year, will be boosting staff when the extra production kicks off," said Stein. What of concerns that the Parsons deal is about lifting technical knowhow from the firm, and using the brand name in production outside Germany? Stein says he's confident that the new owner will protect its German investment and "not squeeze it to death in two years." The Germans have also secured a boardroom guarantee: Though Parsons controls two-thirds of the shares, major strategic decisions require the support of 75% of board members, and thus family approval through the family's remaining one-third stake. "We have written agreements that our pianos will only be built in Braunschweig," said Stein.

Questioning Voices

Not everyone is so confident. Once upon a time, Julius Feurich attended Musikmesse to represent his family firm, founded in 1851. Today he laments that, since 2012, the instruments that carry the Feurich name have been made in China, by Hailun. In Frankfurt, he is representing Seiler, founded in Germany in 1849 but, since 2008, owned by Samick, of South Korea.

"Of course, there's a certain melancholy that I'm no longer building pianos myself," says Feurich. He accepts responsibility for the loss of his firm, but wonders aloud if things might be different today had German piano companies created a shared production facility, making standardized piano parts for less-expensive instruments — he calls them "bread and butter pianos" — now imported from Asia. He remembers such talk in the 1980s and '90s, but it came to nothing. "German piano companies' rivalry in the past was too great," he says. "We were doing too well to agree on something farsighted like that."

Bayreuth piano builder Udo Schmidt-Steingraeber, sixth-generation head of Steingraeber & Söhne, agrees in part with Julius Feurich that German piano firms missed a window of opportunity. He dates this to the decade between two German industry crises — in 1983 and 1993 — when there was talk of closer collaboration for a "Made in Germany" consumer piano. "The talk was there and never realized, though I don't think we would have come in under €10,000. After the 1990s crisis, the moment had passed."

However, their analysis draws strong disagreement from Christian Blüthner. He and his brother Knut head a family piano company in Leipzig that has survived two World Wars and one Cold War. Blüthner dismisses joint-production talk, saying similar efforts didn't work in Germany's crisis-wracked 1930s, and wouldn't work now. Today's piano market is a survival of the fittest, he says, and his German competitors are losing their independence because they failed to diversify and embrace China on their own terms; now they're being squeezed back.

Blüthner was early to spot the rise of China, and 20 years ago started a joint venture there. When the firm realized that this setup endangered its technical knowhow — stealing foreign technical knowledge was a widespread practice at the time, and not only in the piano industry — Blüthner opened its own production facility in China for its lower-cost brand. It now sells 9,000 Irmler-branded instruments annually, primarily in China, and thus has gained a foothold in a distribution network across this vast and growing piano market. Taking his own advice about the need to diversify, however, Blüthner says that Asia makes up just a quarter of his business; the rest is evenly distributed among the U.S., Europe, and the rest of the world.

Given what he says have been the broken promises of previous Chinese investors to preserve the integrity of German subsidiaries, Blüthner is skeptical of the assurances made to Schimmel and Grotrian-Steinweg: "No Chinese company buys a German company to keep losing money. They buy a brand and its associated image to produce the product at lower cost, with lower-quality materials and often without the expensive German labor. If Pearl River decides to build a ‘Josef Schimmel' piano in China, they won't ask Braunschweig, they'll just do it. They'll sell it as a one-off ‘special edition,' but that is where the brand dilution begins."

Blüthner's comments point to what is perhaps the larger and more serious consequence of globalization for the prestigious German brands, even for those that remain under German ownership: the potential damage to a brand's reputation from the increased East-West hybridization of production, especially when it occurs without full and honest disclosure to the consumer. He already sees in some of his German competitors a slow shift to a new production model that makes use of lower labor costs in Asia, and takes advantage of European Union and German laws that allow considerable elasticity in what qualifies for the attribution "Made in Germany." In an obvious reference to a competitor who, Blüthner says, is quietly selling under one of its own brand names pianos that are largely made in China, but at a made-in-Europe price, he adds, "A premium product has to be authentic, and if it doesn't fulfill what it promises or costs, it will eventually backfire. These days, with the Internet, lies have short legs."

But even Christian Blüthner concedes that the takeover of a famous European piano brand by outsiders doesn't inevitably dilute the brand. Sometimes, he says, a takeover gives a company a new direction and preserves a tradition that might otherwise have been lost. For example, in 2008, Yamaha, of Japan, bought the renowned Austrian firm Bösendorfer, and so far there has been no suggestion from any quarter that the quality of instruments or brand has suffered. Likewise, the judicious lending of a famous brand name in support of a less-expensive one doesn't have to endanger the famous brand, as demonstrated by Steinway & Sons, which, for more than two decades, has been displaying "Designed by Steinway" in connection with its Boston pianos (made by Kawai) and its Essex pianos (made by Pearl River).

Nor does expanding the use of prestigious brand names into lower-price markets have to be sneaky. Schimmel already produces a lower-cost brand, Wilhelm Schimmel, in Poland, where lower labor and other costs result in a piano 30% less expensive than its German-made instruments, and the company is completely transparent about this arrangement. Samick, which owns Seiler, makes versions of the Seiler brand under the names Eduard Seiler and Johannes Seiler in its Indonesian facility. Again, the company is completely open about the origin of these instruments in its sales presentations. In each of these cases, the company is taking a calculated risk, but the results undoubtedly vary.

Pragmatic Adaptation

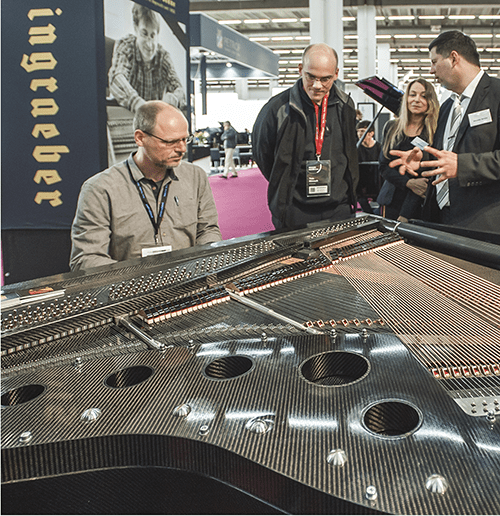

Given the emotional and divided opinions about the role of China in their piano industry, one conciliatory German voice is that of Udo Schmidt-Steingraeber. His firm is one of Germany's smallest, making only about 80 grands and 60 verticals annually. On a sliding scale of views, ranging from sentimentalist to pragmatist, the sixth-generation piano builder from Bayreuth places himself right in the middle. The only way to secure Germany's piano industry, he says, is to embrace change without abandoning tradition. He offers his own 36-person operation as an example: The company's work practices, largely unchanged since the 19th century, have not prevented it from embracing innovations — from carbon-fiber soundboards to Bluetooth pedal switching for wheelchair-bound pianists. "Our small size is problematic in one sense," Schmidt-Steingraeber says, "because it gives us a smaller market share. Yet it has led to a pragmatic search for specialties that others actually cannot manage because of their size."

Steingraeber is no stranger to the Chinese piano giants. In 2008, the Bayreuth firm entered into a partnership with Pearl River to build concert grands for the Chinese market under Pearl River's Kayserburg brand. A letter of intent signed in 2015 promised further cooperation between the two companies. Schmidt-Steingraeber says, however, that all that came to nothing when he declined to sell Pearl River a stake in his company, and the partnership ended last year, with Pearl River's purchase of Schimmel and its plans to transfer its European production to Braunschweig.

Schmidt-Steingraeber suggests that, rather than obsess over the arrival of Chinese investors, German companies would be better off working to maintain two factors that make the German piano industry unique: its respected tradition of training piano builders, and its infrastructure of makers of piano parts. "No piano is a just a collection of its parts, but our supplier infrastructure — makers of hammers, strings, and cast-iron frames — is a crucial backbone of the German piano industry," he said. "Having these firms here enables us to do what we want to do."

Another firm whose relatively small size may be a blessing in disguise is August Förster. Founded in 1859, this eastern German company has survived historical highs and lows and, since 2000, is back under Förster family ownership. It does steady business — 110 grands and 150 uprights annually — by watching costs, staying focused, and avoiding experiments. Annekatrin Förster says that her firm rejects Chinese production and, like Steingraeber, embraces the German piano-making tradition. As long as this tried and tested apprentice/master piano-building system survives, she says, Förster will too. "We want to stay as we are, and our customers want that too." The secret of her family firm's continued independence? She thinks for a moment, then smiles. "Perhaps it helps that we've stayed modest."

Listen between the lines at Musikmesse and it's clear that much of the controversy centers on the role of pride in the German piano industry: How much pride can German piano companies still afford to have in their instruments — and how much can they charge for that pride? Will their pride save the remaining German firms, or be their undoing? Some well-placed German piano dealers argue that it was pride that led to the fall of key industry players in the first place. "For too long, German piano companies sat high on their horse, thinking they were world class and no one else could do what they do," said Matthias Vorndran, managing director of Piano Center Berlin, a dealership in the German capital, who worked for 18 years at Czech piano company Petrof. "The Germans realized too late that Europeans wanted cheap — and they weren't able to deliver."

Back at Grotrian-Steinweg, Burkhard Stein agrees that his business is a bare-knuckles battle with little room for sentimentality: "Of course, I would prefer to say we were still an all-German piano company, but if we went to the wall in five years, that wouldn't be much use." What does he see in the future? Regardless of his company's new owner, Stein is confident that anyone seeking a high-quality instrument will continue to look to Germany. "But if that is still the same in 20 or 50 years, I cannot say," he adds.

Udo Schmidt-Steingraeber is also optimistic about the future of Germany's piano industry — because of one curiosity about the Chinese: Though they are now the world's largest makers and buyers of pianos, China still has no training program turning out people who can build instruments of the highest quality. "They don't even have a school, and that will take at least a generation to change," he said. "Parsons and Pearl River have noticed that they can only achieve the next leap in quality with German teams and with production outside of China. That, for me, means that production in Braunschweig is secure for Grotrian-Steinweg and Schimmel."

At the end of a long day at the Frankfurt Musikmesse, the din is diminishing somewhat, and Hannes Schimmel-Vogel has invited clients and friends for drinks at his company's stand. Among the clinking glasses and the back-slapping, however, one guest is noticeably absent: the company's new owner. Over at the Pearl River stand, June Wang has no time for drinks. After hours on her feet, she's still working, smiling and chatting with a steady stream of visitors. With no visible sign of fatigue, she confidently declares: "The history of the piano is European. The future is Chinese."