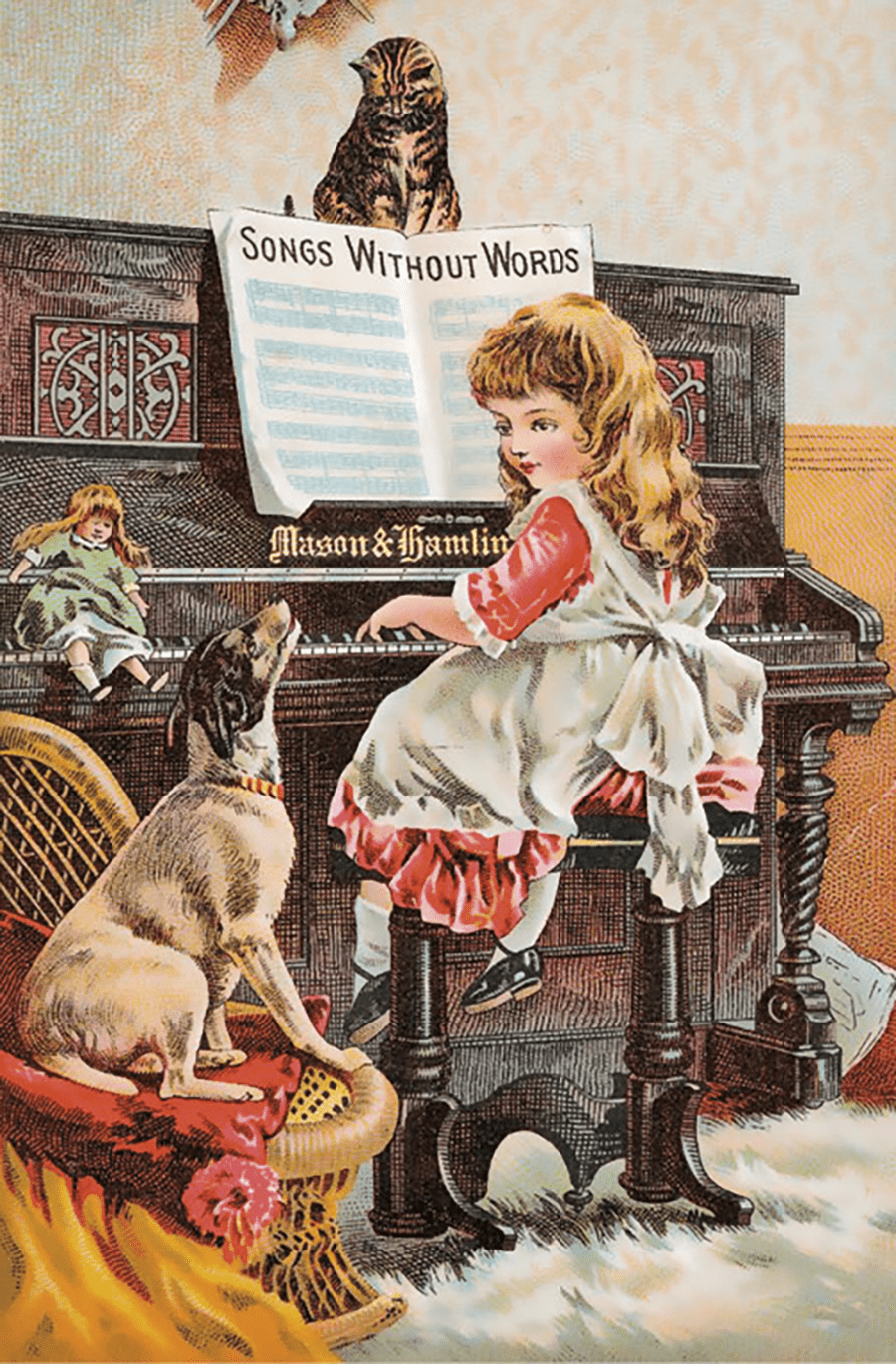

Mason & Hamlin poster, 1887

It's also rare to get the sound in new pianos that vintage instruments produce, say Sara and Irving Faust, of Faust Harrison Pianos in New York City, a dealership renowned for high-level restorations. "The old Steinways, produced in the late 1800s and early 1900s, have never been surpassed," says Sara. "They have warmth, soul, what I would call a sort of ‘three-dimensionality' and color in the sound that you can't find in a modern instrument. And each era seems to have its own special quality. Starting in the 1920s, the Steinway sound became more extroverted. Steinways of the 1940s are both lush and bold. Most importantly, in the hands of a top piano restorer the special rich, mellow, colorful tones of the older instruments are retained. They may look, feel, and smell like new pianos, but they sound like wonderful old pianos.

"You have to have a very large sample to appreciate this fully," Faust continues. "I'm making these judgments based on working with thousands of pianos." The exact reasons why the old Steinways sound different from today's instruments remain a mystery; one theory attributes it to changes in the manufacture of the cast-iron plate that sits at the heart of the instrument.

At Cunningham Piano Co. in Philadelphia, founded in 1891, co-owner Rich Galassini agrees that there are differences among Steinway pianos made at different times. "The final product depends on choices made in materials, design, and the execution of these designs in manufacturing. Any change, intentional or unintentional, in any of these categories will result in a difference in performance.

"But I wouldn't single out just one brand," adds Galassini. "There are a number of beautifully made instruments that historically have had their own voice and, restored, have wonderful performance potential." Galassini would include in this list such venerable brands as Mason & Hamlin, Bösendorfer, Blüthner, and Bechstein, as well as the slightly lesser-known Chickering and Knabe, among others. "There is a very wide palette of tone and touch available to a pianist who wishes to seek out an older instrument that speaks to him or her personally."

This 1915 Steinway advertisement reflects the prevailing sentiment of the time--that developing her musical skills would increase a young woman's chance of a good marriage. (Source: NW Ayers Advertising Agency Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Steinway's Bill Youse has a somewhat different perspective. There may be differences in quality between older instruments and today's, he says, but it's difficult to render an opinion because, "by the time I get them, they are in demise." More likely, the perceived differences have to do with changing aesthetics, he adds: "The tonal requirements today — the sounds people are looking for — are different than they were years ago. Today we juice the hammers to produce a brighter sound. We tune at a higher pitch. Sometimes it's too harsh for my senses. I like pianos voiced in a mellow way. But the entire piano industry has developed that trend toward brightness."

Perhaps because of these different outlooks, the three firms have different approaches to restoration. "We replace rather than repair," reports Youse. "We retain original parts only in a museum-type restoration, as we did for the White House piano, and the ‘Peace Piano' — the one with gold stars all around that had been in Congress and that now resides at the Smithsonian Institution. When we worked on the ‘King of Sweden' piano, which arrived with envoys and armed guards, we of course had to use the original types of glue and varnish. But in most cases, we believe that newer is better.

Installing new hammers on a Steinway grand

"There is a perception that the old craftsmen did it better," Youse continues. "Yet the materials we use, and the ways we have of testing things, have gotten better. We replace hardware, to avoid sympathetic vibrations that develop as things wear. The modern action is an improvement over older ones.

And our wood technologist tells me that after about 60 years the cellular structure of spruce breaks down, and the soundboard just won't have the same resilience. The newer ones are superior."

At Faust Harrison Pianos, standardizing parts is not always considered the right way to go. Indeed, their technicians often mix replacement parts — combining elements of Renner and Steinway, for example — to achieve the desired results. Rather than replacing items wholesale, they may design individual solutions for each area of the instrument being serviced, in order to accommodate the original dimensions and materials, or to maintain the look of an earlier design.

Cunningham, too, takes a more customized approach to restoration. "All manufacturers change the design of their pianos over time," says Galassini, "in part to improve their instruments, but also in an attempt to appeal to the fashionable tone of the time." Because of this, rebuilders must decide if they wish to be faithful to the originally intended design, or if they wish to make the piano sound more modern. "For instance," says Galassini, "a welleducated rebuilder, if he wanted to, could reproduce the tone and touch of the Mason & Hamlin that so moved Ravel."

Of course, all of these companies employ expert workers. One particular Steinway restorer, brags Bill Youse, can make anything seem new again: he once repaired a mummy that had lost a leg in transit. Another, he claims, "can duplicate any painting you show him." That comes in handy when the piano to be worked on is an "art case" instrument: one of those exquisitely designed models, often decorated with paintings or built with rare woods, that emerged in the 19th century — a piano-building tradition recently resurrected at Steinway. These pianos, with their highly artistic cabinetry, can be extraordinarily attractive — and valuable.

That touches on a third reason to seek historic instruments: their monetary value. Older instruments may be of a rare vintage, or possess an unusual pedigree. In any case, as remnants of a more genteel age, when pianos held a prominent place in nearly every home, they nearly always carry an aura of romance.

In fact, good Victorian families set aside a formal area for piano entertaining, which was once the best way to demonstrate a flair for stylish living. The evidence can still be found in the preserved dwellings of important figures from the past, including Mark Twain, whose home in Hartford, Connecticut, featured a Steinway & Sons baby grand used for recitals organized by his wife, Livy; and Louisa May Alcott, who, when not walking to Walden Pond for boat rides with Henry David Thoreau, played a Chickering square piano in her parlor. Emily Dickinson kept a Wilkinson piano in her Amherst house, and Edna St. Vincent Millay had two Steinways. Eugene O'Neill loved his player piano — a coinoperated instrument with stainedglass panels — and named it "Rosie."

Surprisingly, the piano wasn't instantly popular. Though its official birth date is generally agreed to be 1700, in many ways the piano was still in its infancy at the end of the 18th century. In London, the instrument's public debut as a solo instrument didn't take place until 1768 (Johann Christian Bach had the honor). Leading craftsmen in the decades that followed produced no more than 30 to 50 instruments a year. But a great wave was coming. By 1798, English piano maker James Shudi Broadwood could not keep up with demand. "Would to God we could make them like muffins!" he wrote to a wholesaler. Five decades later, the desire for pianos had exploded: England was suddenly the center of the piano world, with some 200 manufacturers. And, with increased production, large segments of the population could now afford to purchase one.

No wonder George Bernard Shaw wrote that, in the late 19th century, piano playing had become a "religion." The instrument served every musical and social need, making it possible to learn and perform great works, strengthen family ties, and impress the neighbors.

Keyboards have enjoyed a long history as symbols of prosperity. The piano art case, in fact, had its origins in the 16th and 17th centuries, when harpsichords were adorned with paintings, often of Orpheus charming the animals or battles on horseback. Sometimes they were also inscribed with mottos: "I was once an ordinary tree," read one, "although living I was silent; now, though dead, if I am well played I sound sweetly."

The instruments then were intended primarily for the women of the household, and the piano boom was similarly helped along by young ladies of a certain social status who were taught that developing their musical skills would increase their chances of a good marriage. As late as 1847, critic Henri Blanchard, in France, reported that "Cultivating the piano is something that has become as essential, as necessary, to social harmony as the cultivation of the potato is to the existence of the people. . . . The piano provokes meetings between people, hospitality, gentle contacts, associations of all kinds, even matrimonial ones . . . and if our young men so full of assurance tell their friends that they have married twelve or fifteen thousand francs of income, they at least add as a corrective: ‘My dear, my wife plays piano like an angel.'"

The attractiveness of the instrument as a piece of furniture was also important. The wood, ivory, and artistic detail of a fine instrument lent elegance to a home. And, as a center of attention, it cried out for special enhancements. England's Mrs. Jane Ellen Panton pointed out, in her authoritative From Kitchen to Garret (1888), a bestseller of the era, that it was a good idea to decorate one's piano with material "edged with an appropriate fringe," and to place a big palm in a brass pot into the bend of the instrument, to give it "a finished look." Victorian prudishness also sometimes came into play, with suggestions that coverlets be put over the piano's legs for the sake of modesty.

Some piano makers even designed special models with the homeowner in mind. An "upright grand Pianoforte in the form of a bookcase" was patented by William Stodart in 1795 (there is evidence that Haydn visited Stodart's shop and approved of the device); and the early 19th century saw the introduction of a square piano in the form of a sewing table. Highly decorated upright pianos featured giant lyres, arabesques, and flutings; one extant sample includes a medallion bust of Beethoven.

It didn't take long for the piano to gain a foothold in the New World as well, where it reached beyond the big cities into America's western territories. "'Tis wonderful," wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson in Civilization (1870), "how soon a piano gets into a log-hut on the frontier." We can glimpse the results in diaries kept by American homesteaders. Living in the mining town of Aurora, Nevada in the 1860s, a Mrs. Rachel Haskell recorded that in the evening, after dinner, her husband would come into the sitting room and place himself near the piano as their daughter, Ella, accompanied the entire family in song. Rachel's daytime regime included instructing Ella at the piano, along with practicing the multiplication tables with her sons, making dinner, and visiting friends.

This trend caught the attention of W.W. Kimball, who settled in Chicago in 1857 and announced that he wanted to sell pianos "within the reach of the farmer on his prairie, the miner in his cabin, the fisherman in his hut, the cultivated mechanic in his neat cottage in the thriving town." He based his new business on the installment plan — as did D.H. Baldwin, a Cincinnati dealer who, in 1872, hired an army of sewingmachine salesmen to recruit new customers.

The piano in America continued to be seen as a tool to regulate the life of the tender sex, just as it had across the ocean. The critic of the New York World, A.C. Wheeler, laid out the argument in 1875: "[It] may be looked upon as furniture by dull observers or accepted as a fashion by shallow thinkers, but it is in reality the artificial nervous system, ingeniously made of steel and silver, which civilization in its poetic justice provides for our young women. Here it is, in this parlor with closed doors, that the daughter of our day comes stealthily and pours out the torrent of her emotions through her finger-ends, directs the forces of her youth and romanticism into the obedient metal and lets it say in its own mystic way what she dare not confess or hope in articulate language." Through the early decades of the 20th century, pianos continued to be built — and to be played — in this cultural atmosphere of naïveté and old-world charm. We live in a very different world now: one filled with iPods, interactive games, and — for pouring out torrents of emotion — talk therapy. But the gracefulness and enchantment of that earlier time still imbue many of the instruments it produced.

Restoring those pianos to their full beauty can be a painstaking process, as one quickly discovers when touring the sprawling restoration facility of Faust Harrison Pianos in Dobbs Ferry, New York, where each aspect of piano rebuilding warrants its own room. There is a lot to consider. "Take the hammers," explains Sara Faust; "they each have to hit the strings at the optimum point for sound production. Yet if they are placed optimally, you may not see a perfectly straight hammer line, but something that resembles a gentle roller coaster, particularly in the third register. Sometimes technicians try to compensate for a weak sound by putting extra lacquer on the hammers, but the right answer is often not lacquer at all, but to make an adjustment to the strike point. Indeed, minimally lacquered Steinway hammers have a special beauty that should be preserved whenever possible. A new hammer may start out like a closed rosebud, but as it is played it hardens naturally from compression, and the sound opens up and blossoms.

"And new hammers have more wood than old ones," she continues, "so we sometimes remove some wood, changing the mass and shape of the hammers, to clarify the sound. Why do we drive ourselves crazy in this way? Because when you have a well-crafted hammer, the piano can sound both more beautiful and more powerful at the same time."

In the "rubbing room," a series of sandings, using finer and finer materials, ensures a beautiful cabinet surface. But there are dangers here as well: in the wrong hands, important cabinet details in a vintage artcase instrument can be lost. A good restorer will bring them back.

It all has to be done with a light touch, inside and out. At A.C. Pianocraft, in New York City, owner Alexander Kostakis explains that "The instrument will tell me what to do. I have to keep everything in perspective. Each instrument has a personality, or ‘soul.' We have restored all the American and European brands of yesteryear — Steinways, Mason & Hamlins, Bechsteins, Blüthners, Pleyels, Knabes, Chickerings. Each one is different, and the experience has made us better mechanics, more versatile.

Replacing a pinblock in a grand piano

"For example, old pianos had a flat inner rim where the soundboard was attached. But sometimes, when restoring the piano, we've added a pitch to the rim to give the soundboard more resonance. As for replacing parts, you always have to remember that the perishable items within an instrument have a certain lifespan. But we also try to maintain the authentic character of the instrument, and sometimes choose to repair rather than replace."

In a business driven mostly by a love of the instrument, piano restorers sometimes seem to work miracles. Even so, there are limits to what can be accomplished. "Some brands you'll restore once, but never again," says Kostakis — "every time you touch something, something else breaks. But we've also had amazing successes. I advised a customer not to restore a family heirloom: a Kranich & Bach Louis XV model in walnut. It was a beautiful piece of furniture, but it looked like restoring the action would be impossible because no one makes the right parts anymore. But the customer was adamant about restoring the instrument, so we agreed to repair the action parts rather than replace them. Working on the piano, however, I realized that the old action parts, even repaired, would never be good enough, and might give trouble later on. It was a Herculean task, but in order to do the right thing for the piano and for the customer — and, frankly, to sleep well at night — I actually reproduced brand-new parts in the exact style of the old ones."

Steinway, too, has seen its share of horror stories. "There was a church down in Georgia," remembers Bill Youse; "they had a Model O that had been badly damaged by a fire, and they wanted it restored. I asked for a photo. All that was left was the harp and a bunch of burnt strings sticking up. They were essentially asking us to build a piano around the old harp — an impossible task."

Still, had the assignment been humanly possible, he would have tried. "I love my job," he says. "I'm third generation here at Steinway. My grandfather was a blind tuner back in the late '40s. My father started here in 1955. I've been here 37 years. For me, this is an honor. My first bicycle was a beat-up model I had to restore. My first car was a beatup old Chevy I had to restore. This was a natural progression. It's what I was meant to do."