Our music rooms, whether large concert halls or smaller spaces in the home, can help or hinder our performance. Too large a room can strip our sound of energy and resonance, while too small a space can cause sonic overload, making the sound muddy, harsh, and overbearing. To enable an instrument built to fill a great concert hall to also work in much smaller domestic spaces and studios requires proper planning. Do you want to practice in an environment in which clarity of sound is more important than volume and resonance, or do you want to be able to play solo and chamber-music concerts in your home, in emulation of a small concert venue? These will require different approaches to room design, and possibly the choice of instrument.

The art of acoustical design for live music is part science, part empirical knowledge, part musical intuition, and part common sense. I call it an "art" mainly because one has to be creative when working in a space that needs to be both sonically and aesthetically pleasing. After all, few piano owners want to see their living rooms turned into sound laboratories simply to achieve their desired musical goals.

Based on my twenty-five years of experience as an acoustical consultant, as well as a professional musician, in this article I will tell you about the things you can do yourself to improve the acoustical qualities of your piano room. However, if you plan to buy a larger, higher-quality grand piano, I suggest that you consider allocating some additional funds to have your room tuned by an acoustical professional or by a contractor experienced in the acoustical treatment of small music rooms. Acoustical treatment techniques have come a long way in recent years, and there are many products that can be integrated into just about any domestic environment without making the room look like a recording studio. I have done this many times, without sacrificing musical or visual aesthetics.

Room Size

Vertical pianos are designed to work optimally in smaller rooms. They are usually placed up against a wall, and present relatively few problems in the typical domestic environment. The same is true of small grands. But the amount of sonic energy produced by anything larger than about a 6-foot grand can present some big problems in smaller rooms. While concert halls and piano showrooms are big enough to allow the sound of a larger grand to properly resonate, small rooms can't absorb so much sound, and will easily overload when the instrument is played full out. Like other fine musical instruments built to be played in large spaces, a large grand sounds best from some distance away. For instance, stand next to me when I play my contrabassoon's lowest B-flat (half a step above the lowest A on a piano), and while you can physically feel the power of that note, you won't be able to decipher its actual pitch until you walk several feet away from the instrument. The same thing occurs with a double bass, tuba, or pipe organ. At the opposite end of the scale, a really fine violin won't sound its best until the listener is several feet away, when the sound becomes more resonant, with more clearly defined pitch. This is the situation we face when placing a large piano in a room smaller than it was designed for. While we can do many things to just about any room to make it more friendly to a large piano, there are limits, dictated by the laws of physics, that we can't break without paying a price in quality of sound.

How large a piano room needs to be depends on the size of the instrument. Empirical data indicate that the combined length of a room's walls (assuming that the room's ceiling is 8 feet high) should be at least 10 times the length of a grand or the height of a vertical piano. For example, a 15 by 20-foot room (15+15+20+20=70 feet) should accommodate a 7-foot grand. This formula doesn't take into account openings into other rooms, irregular room shapes, etc., but it's a good starting point.

Low frequencies have the longest wavelengths and cause the most problems in smaller rooms because the length of the wave exceeds the largest dimension of the room. The lowest A on a piano has a frequency of 27.5 Hz (cycles per second), which translates into a wavelength of about 41 feet! For this reason, the lower two octaves of a 7-foot grand, having less sonic power, will probably sound clearer in a small room than those of a 9-foot instrument in the same space, even though the larger instrument has the potential for greater low-bass clarity. This is the same principle that applies when designing audio systems and home theaters. In a smaller room, a smaller loudspeaker that pressurizes less air to reproduce a given frequency will actually sound clearer and deeper than a far bigger speaker in that room, even if the larger speaker's bass can go a bit lower in pitch. Therefore, common sense tells us that putting a full-size 9-foot concert grand into a 12 by 15-foot room with an 8-foot ceiling will probably not yield the best results without a huge amount of dedicated acoustical treatment, and probably not even then.

If your piano room is L-shaped, or opens into another large space, this can help your piano's low-octave bass response — the much-longer low-frequency soundwaves can travel through large open spaces. This is one reason why, in a small room, opening the doors to adjacent rooms can often make your piano's low octaves sound a bit clearer. (Because the shorter, high-frequency waves tend to bounce off any flat surface closest to the piano, the extra space won't improve their clarity.)

Try to avoid square rooms, or rooms with wall lengths and ceiling heights having a relationship of 1:1, 1:2, or multiples thereof (for example, 16 feet long by 8 feet wide by 8 feet high). Such rooms exacerbate the buildup of low-frequency coincident modes (resonant frequencies caused by standing waves), which can make the lowest octave of your piano sound uneven, overemphasizing some notes while making others virtually disappear.

Ceiling Height

Greater ceiling height is always desirable for resonance, but be careful with this. As mentioned above, it's best that the ceiling height not be the same as the length of one of the walls, or that length divided or multiplied by 2 or a multiple of 2. For example, if one wall is 16 feet long, the ceiling should not be 8, 12, or 16 feet high. If your ceiling is more than one-and-one-third times the length of the shortest wall, you may have a problem of reflected soundwaves that will require some dedicated acoustical treatments, though not necessarily. I've worked in some rooms with very high ceilings that sounded fabulous, mainly because the extra headroom helped the low notes sound more full and deep. It all depends on how "live" (resonant) the space is, and exactly which room surfaces are reflecting the sounds of the piano. If you have a sloped ceiling, the best results will likely be achieved by placing a vertical piano against the wall where the ceiling is lowest, or a grand piano facing out from the same wall and into the area where the ceiling is highest.

Where to Place the Piano in the Room

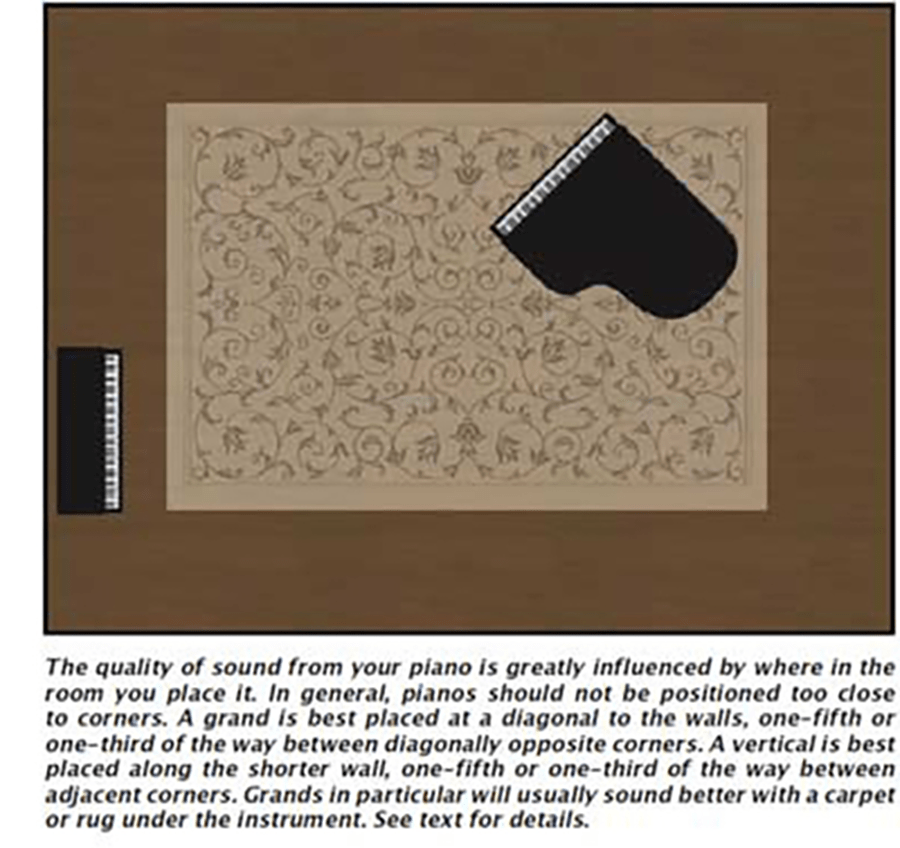

Try not to push the tail of a grand, or the end of a vertical, all the way into a corner of the room. While doing so might give the lowest octave more power (low frequencies are boosted by adjacent wall and floor surfaces), pitch clarity and tonal evenness will suffer. The hard sound reflections coming off both corner walls can also kick back into the player's ears a lot of high-frequency "hash." Vertical pianos are best placed against a room's short wall, with the center of the piano one-fifth or one-third of that wall's length from the nearest corner. Try the instrument in both locations, listening for evenness of tone across the scale. Then slowly move it, a few inches at a time, in either direction to fine-tune the sound for clarity.

Finding the right spot in the room for a grand piano involves some effort but is not difficult. Begin with the piano near a corner of the room; if possible, position it with the long side across the corner at a 45° angle to the walls, with the open lid facing out into the room toward the diagonally opposite corner. This will keep both ends of the piano equidistant to the walls and corner behind the instrument, enhancing evenness of tone throughout the piano's frequency range.

Now, measure the distance between the corner behind the piano and the diagonally opposite corner. Then, keeping the piano at a 45° angle, move the piano one-fifth of that distance out from the corner, in the same direction you just measured. Open the lid and play scales through the instrument's entire range, listening for even tonal quality and clarity of pitch. Then move the piano farther in the same direction, until it's now one-third of the way out from the corner. Play it again. Then, placing the piano in the best-sounding location of the two, slide it, in very small increments, back toward the wall closest to the keyboard end of the piano, maintaining the 45° angle, and playing the same scales after every change in position. Then, once you find the "sweet spot," begin slowly rotating the piano by moving the keyboard end very slightly, a few inches at a time, in either direction, playing the same scales every time. This procedure can take some time, but it's well worth the effort, and not as difficult as it sounds. You'll probably be amazed at how big a difference very small changes in position can make in the way your piano interacts with the room boundaries. While this may not solve all of your room problems, I have yet to find a situation where it didn't significantly help.

Reflection, Diffusion, Absorption

Sound behaves in much the same way as light. Shine a flashlight at a mirror in a dark room, and a hard glare will be reflected right back into your eyes. Shine the same flashlight onto a frosted piece of glass, and you'll notice that the light is evenly distributed in a pleasing circle on the surface of the glass, which will also reflect more light around the dark room than the mirror did. Apply this to music in an enclosed space, and you can understand why diffusion — the random scattering of sound — is far better than hard reflection. The latter makes the music itself sound hard and brittle, while diffusion provides clarity, warmth, and an evenness of sound throughout the room. And because diffusion more evenly distributes high- and mid-frequency sound throughout a room, it adds greatly to musical clarity.

Absorption is useful in reducing the amount of sonic energy in a room. Many people make the mistake of cutting down reflections by deadening their music rooms with heavy draperies, thick carpets, and overstuffed furniture. However, this will not absorb all frequencies evenly, and can make a room sound dull in the upper octaves and too heavy in the bass — or the other way around. While in "live" rooms some absorption is desirable, even necessary, I suggest a combination of absorption and diffusion. This can be done by placing books, bookcases, artworks, chairs, and other randomly shaped objects along the walls to break up reflections, as well as scattering around the room some soft surfaces, such as upholstered furniture. Some of the best music rooms have mostly hard surfaces with little absorption, but they all have many diffusive surfaces that break up the reflections, which keeps the sound live, warm, and resonant. Partially closed wooden blinds or other irregularly shaped treatments for windows and glass doors will help diffuse reflections coming off of those glass surfaces. Note that flat artworks, even when not covered with glass, can cause degrading reflections unless they have a very irregular diffusive surface. Fabric wall hangings, especially quilts and other thick, soft, irregular surfaces, can absorb a lot of high-frequency reflections, when used in moderation — but not heavy drapes, unless the room is especially "live" and reverberant.

______________________________

Floor Coverings

What you put under your grand piano can make a huge difference in its sound. In designing a music room, whether or not it will contain a piano, I normally specify hard floor surfaces, whether of hardwood, ceramic tile, or marble. The center of the floor should be covered with an acoustically absorbent surface, such as a carpet or rug. The idea here is to have sound absorption in the central part of the floor to cut down on reflections, while keeping the edges of the room more "live" for resonance. If the best-sounding location for your piano is not far enough out into the room for the instrument to be placed on the carpet or rug, place under the piano a separate area rug large enough to cover the piano's entire footprint. The bottom of a grand piano's soundboard produces a great deal of sound that a hard floor will reflect, thus making the sound harsh and brittle — unless something is there to help absorb that energy. If you don't mind how it looks, you can store piles or boxes of music or recordings on the floor directly under the piano, which will provide absorption and diffusion. In very "live" rooms, a thick fabric cover (similar to a full piano cover) can be suspended under the instrument's soundboard. This is especially useful in practice rooms, where clarity is more important than generating a big sound.

Vertical pianos, normally placed against or near walls, don't interact with hard floor surfaces as intimately as do grands. However, if your vertical is in the middle of a very "live" space, such as a dance studio or theater rehearsal room, it can benefit from some sort of floor covering under it that extends a few feet out from the piano on all sides. If a vertical's sound is still too resonant or bright, whether the piano is up against a wall or out in the middle of the room, you can eliminate some of this by hanging a heavy fabric cover or blanket over the back of the instrument. Not very stylish, but it works.

Some high-end piano dealers will give you time to audition an instrument in your home or studio before you make a final commitment to purchase. I strongly recommend taking advantage of any such offer — the room in which you place your piano is as important as the instrument itself in determining the ultimate sound.